What People Miss With Sand Batteries

Social Media is currently obsessed with "sand batteries." On paper, they sound like a miracle: we stop digging for lithium and cobalt and start using the stuff you find at the beach. Of course, how could we all have been so foolish.

The pitch is seductive:

- Dirt cheap materials: It’s literally just sand in a silo.

- Zero supply chain drama: No rare earth minerals or geopolitical bottlenecks.

- Scale: You can build them almost anywhere.

Naturally, the comments section is always some variation of: “Why aren’t we doing this everywhere already?!”

It’s a fair question. But the answer isn't a conspiracy—it’s physics.

The Round-Trip Tax

Here is the part of the brochure that usually gets left in the fine print: Sand batteries store heat, not electricity.

When you want to use a sand battery for the power grid, you aren't just moving energy; you are changing its state. This creates a brutal three-step process:

- Electricity → Heat (Resistance heating)

- Storage (The sand stays hot)

- Heat → Electricity (The "Death Zone")

Steps 1 and 2 are actually quite efficient. It’s Step 3 where the wheels fall off. To get electricity back out of a hot pile of sand, you need a heat engine—a turbine, a Stirling engine, or a thermoelectric system. All of these are governed by the Carnot Efficiency Limit.

In formal terms, the maximum theoretical efficiency (ηmax) of a heat engine is defined by the temperature of the hot source (TH) and the cold sink (TC):

ηmax=1−THTC

In the real world, once you factor in mechanical friction and thermal leakage, you aren't getting 90% back. You’re lucky to get 30% to 50%.

You'd be amazed at the number of Venture Capitalists that don't understand thermodynamics or Carnot Efficiency...

Why "Cheap" Storage Can Be Expensive

If you store 100 kWh of wind power in a Lithium-Ion battery, you get about 90 kWh back. If you store it in a sand battery to run a turbine later, you might get 40 kWh back.

This is not a minor rounding error. It’s a doubling of your upstream costs.

If you lose half your energy in the round-trip, you effectively have to:

- Build twice the solar panels.

- Lease twice the land.

- Pay for twice the transmission capacity.

The "battery" was cheap, but the system just became a nightmare of capital expenditure (CAPEX).

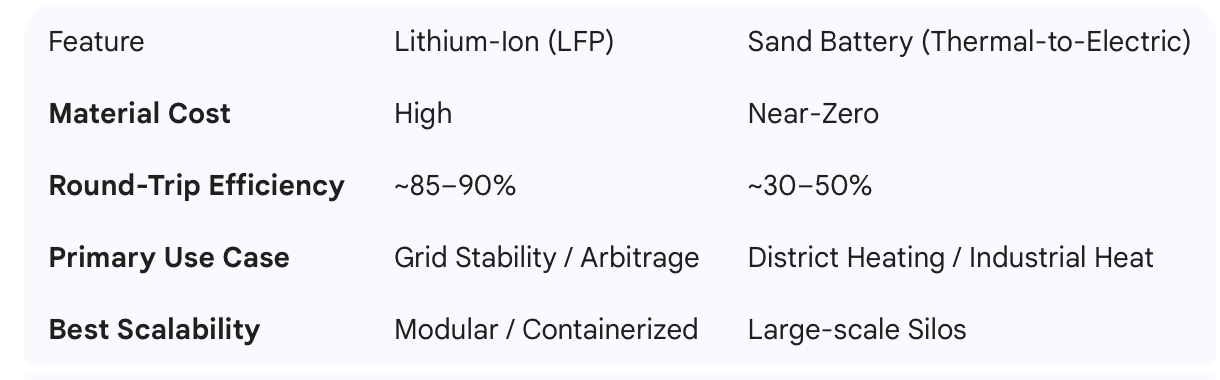

Thermal vs. Electrical Storage: A Comparison

The Category Error

The mistake isn't the technology itself; it’s a category error. We are trying to use a thermal tool to solve an electrical problem.

Sand batteries are brilliant when the "output" is heat. If you are Polar Night Energy in Finland and you’re using that sand to provide district heating for a city, your efficiency is nearly 100%. You’re storing heat and delivering heat. That is a win.

But the moment you try to turn that heat back into a spark for the grid, you’re playing a losing game against thermodynamics.

The Reality: Sand batteries belong in the same bucket as molten salt and hot water tanks—they are thermal infrastructure. They are not substitutes for Tesla Megapacks or high-power arbitrage systems.

It's not about, "How cheaply can we store a Joule?" That’s the wrong metric. We ask: "How many of those Joules can we actually get back when the sun goes down?"

Once you factor in the "Carnot Tax," many trendy storage startups aren't actually solving the energy crisis—they’re just creating a very expensive way to warm up the atmosphere.

Physics doesn't care about your hype cycle.

The Bottom Line

Using a sand battery for grid-scale electrical storage is like putting your paycheck into a savings account that charges a 50% withdrawal fee.

The problem isn't the cost of the sand. It’s the cost of the physics.